- Asia, Close Bases, Japan Chapter, Law, Nonviolent Activism

By Joseph Essertier, World BEYOND War, October 10, 2021

Two hundred residents of Aichi Prefecture, where I live, have just scored a significant victory for peace and justice. As the Asahi Shimbun has just reported, “The Nagoya High Court ordered a former prefectural police chief to pay about 1.1 million yen ($9,846) to the prefecture for ‘illegally’ deploying riot police to Okinawa Prefecture to quell anti-U.S. military protests.” From 2007 until recently, some residents of Takae, Higashi Village, in the Yanbaru Forest, a remote area in the northern part of the Island of Okinawa, along with many peace advocates and environmentalists of the Ryukyu Islands and throughout the Archipelago of Japan, frequently and tenaciously engaged in street protests to disrupt the construction of “helipads for the US Marine Corps, which come as part of a 1996 bilateral deal between Japan and the United States.”

The Yanbaru Forest is supposed to be a protected area and was placed on UNESCO’s “World Heritage List” in July of this year, but right in the middle of the forest causing natural destruction and threatening potential death to residents is a scar on the land, i.e., the largest U.S. training facility in Okinawa, called “Camp Gonsalves” by Americans, also known as the “U.S. Marine Corps jungle warfare training area.” If Washington’s bullying of Beijing sparks a hot war over Taiwan, the lives of the people in that area and all throughout the Ryukyu Islands would be in jeopardy. The Island of Okinawa is more riddled with U.S. military bases than anywhere in the world, and the government of Japan has rapidly built a few/several new military bases for their own military on small islands in the Nansei Southern Island Chain (south of the Island of Okinawa and close to Taiwan). They’ve literally got China “surrounded” now, where “three aircraft carriers – two American and one British – were in the armada of 17 warships from six countries that trained together in the Philippine Sea,” which is just east of the South China Sea.

It is no accident that the first word in the name, or the “banner” one might call it, for our small-but-determined group that has protested almost every Saturday evening for the last few years in Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture is Takae. The banner on Facebook reads, “Takae and Henoko, Protect Peace for Everyone, Nagoya Action” (Takae Henoko minna no heiwa wo mamore! Nagoya akushon). The place name “Takae” in our name reflects the fact that we began gathering on a street corner for protests in Nagoya—for Okinawa—in 2016, when the struggle for the human rights of people in Takae, against war, etc., was especially intense.

The struggle against the other major new base construction project, i.e., the one in Henoko, is still intense. This summer we at World BEYOND War started a petition that you can sign, to stop the construction in Henoko. Unlike Takae, it has not yet been completed. It was revealed recently that the U.S. and Japanese militaries may be planning to share the new base at Henoko.

One of our most committed members, who has engaged in legal, non-violent direct action in Okinawa many times; who is a talented antiwar singer/songwriter; and who kindly filled in for me recently as the Coordinator of Japan for a World BEYOND War is KAMBE Ikuo. Kambe was one of the 200 plaintiffs in the lawsuit mentioned above in the Asahi, where their journalist explains the lawsuit in the following way:

About 200 residents in Aichi Prefecture joined the lawsuit against the prefectural police department. The Aichi riot police were sent to Higashi, a village in northern Okinawa Prefecture, between July and December 2016. Demonstrations were being held there to protest construction of helipads for the U.S. military. The riot police removed vehicles and tents used by the protesters in the rallies. Aichi Prefecture is one of several prefectures that sent riot police to the scene. The plaintiffs asserted that the deployment was illegal and ran counter to the purpose of police to serve the local government.

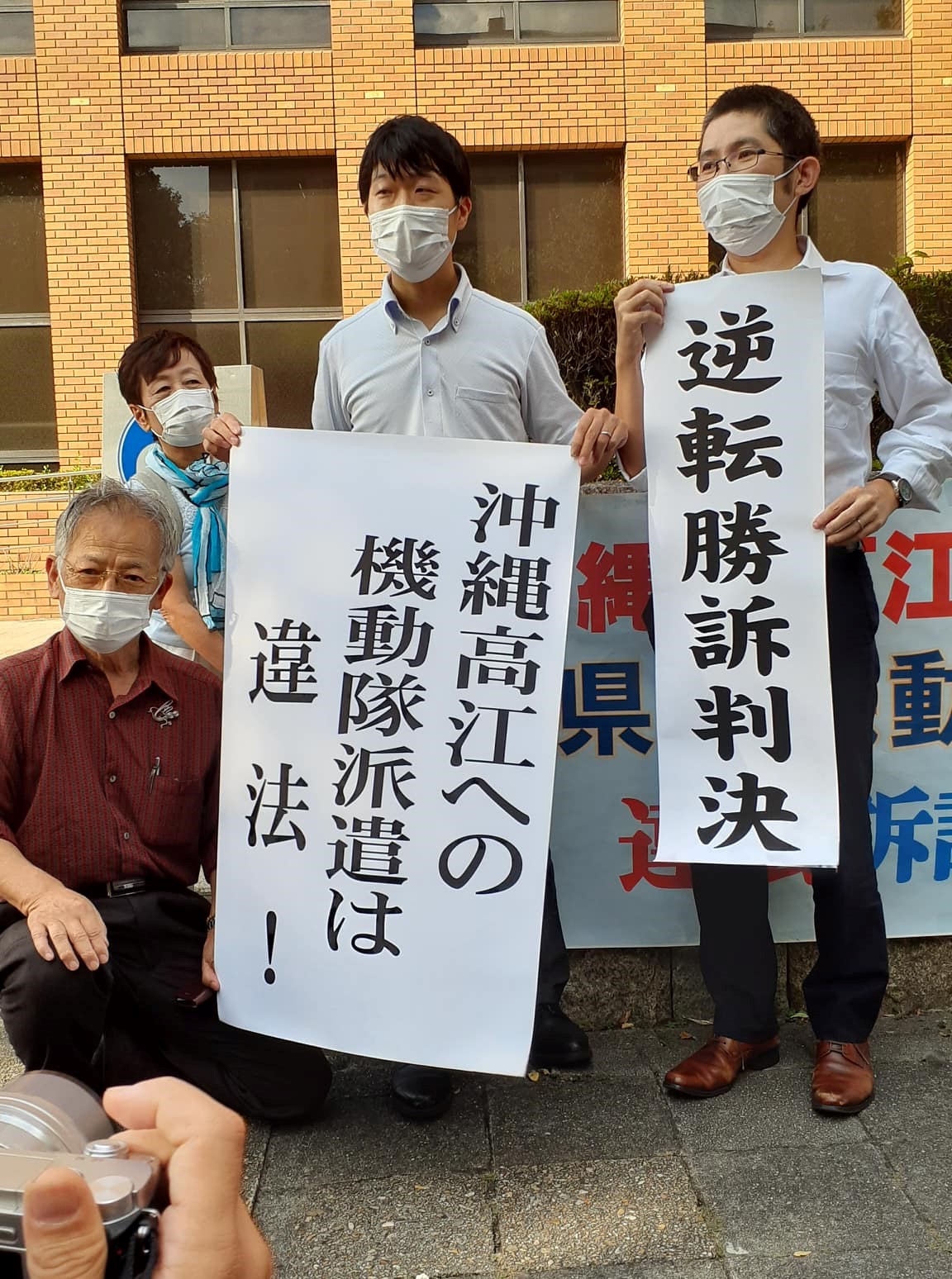

These two signs announce how the court ruled. On the right, the man with the glasses holds a sign with six Chinese characters meaning, ‘Judicial Reversal Ruling.’ The sign that the man holds on the left with many more characters says, ‘The dispatch of riot police to Takae, Okinawa was illegal!’

This is the tent where protestors have gathered in Takae and have sheltered from the rain, etc. The photo was taken on the day when the ruling on Takae was issued in Nagoya, when there happened to be no people at the tent in Takae. The flag says, “Stop aircraft trainings! Protect lives and our life!”

This particular gate to the Takae base is called the “N1 Gate,” and is the location of many protests over the years.

The following text is a translation of Kambe’s report, which he wrote specially for World BEYOND War, and below that the Japanese original. Reports in English on the situation in Henoko are far more numerous than reports on Takae, but the 2013 documentary “Targeted Village” provides a good snapshot of the dramatic struggle in Takae between the agents of peace on the one hand and the agents of violence in Tokyo and Washington on the other. And the 2016 article by Lisa Torio “Can Indigenous Okinawans Protect Their Land and Water From the US Military?” in The Nation provides a quick written summary of the various social justice issues raised by the Takae construction.

A Judicial Reversal!! in the “Lawsuit against the Dispatch of the Aichi Prefectural Riot Police to Takae, Okinawa”

On 22 July 2016, approximately 200 residents of Aichi Prefecture filed a lawsuit against the dispatch of 500 riot police from six prefectures across Japan to force the construction of [the U.S. military] helipads in Takae, claiming that the dispatch was illegal and demanding that the prefecture refund the costs of dispatching the police. We lost our case in the first trial at the Nagoya District Court, but on 7 October 2021, the Nagoya High Court, in a second trial, ruled that the original ruling of the first trial must be changed, that the [Aichi] Prefectural [Government] must order the Prefectural Police Chief, who was the chief at the time, to pay 1,103,107 yen [about 10,000 U.S. dollars] in compensation. The court ruled that his decision to dispatch the police without deliberation by the Aichi Prefectural Public Safety Commission, which supervises the prefectural police, was illegal. (In the first trial, the court had ruled that while there was a legal flaw in what he did, the flaw had been fixed by an after-the-fact report, and thus his decision was not illegal).

The court [in the second trial] also ruled that the removal of tents and vehicles in front of the Takae N1 gate was “strongly suspected to be illegal,” and that police actions such as the forcible removal of sit-in participants, video recording, and vehicle checkpoints “exceeded the scope of the law and they cannot all necessarily be deemed lawful actions.”

Many of the plaintiffs have participated in the sit-ins in Takae and Henoko and have witnessed the illegal and lawless behavior of the police. In Henoko, sit-ins are still held every day, and in Takae, residents’ groups are vigilantly watching [what the Japanese government and U.S. military do]. The court decision declared the dispatch procedure illegal, but I think that we must clarify through this trial what the police are actually doing in Okinawa, and underscore the fact that the illegality of police actions were mentioned in the Court’s judgment. Similar trials have been held in Okinawa, Tokyo, and Fukuoka. Fukuoka lost in the Supreme Court, while Okinawa and Tokyo lost in their first trial and are now appealing those decisions.

The protests in Takae and Henoko have been “non-violent,” “non-submissive,” and “direct action.” To my mind, pursuing the police illegality in court as well as doing sit-ins in front of the gates [to these bases] both constitute “direct action.” It is not easy for me to participate in local actions (in Okinawa), but I am committed to continuing to stand in solidarity with the people of Okinawa and the people of the world, gaining sustenance from the four-year trial for which we struggled under the slogan “not Okinawa’s anger, my anger.”

By KAMBE Ikuo